Category:Heraldry Terms

Contents

From the Persona Guidelines section of the 7.2 Rulebook

A device or insignia to display on your flags, banners, and coat of arms. The device should be unique or at least in keeping with your persona or company. You may register the device with the Guildmaster of Heraldry and the Prime Minister. Japanese Heraldry, or family crests are called Kamon

See Kingdom Heraldry

Heraldry in History

Heraldry in its most general sense encompasses all matters relating to the duties and responsibilities of officers of arms. To most, though, heraldry is the practice of designing, displaying, describing, and recording coats of arms and badges. Historically, it has been variously described as “the shorthand of history” and “the floral border in the garden of history”. The origins of heraldry lie in the need to distinguish participants in combat when their faces were hidden by iron and steel helmets. Eventually a system of rules developed into the modern form of heraldry.

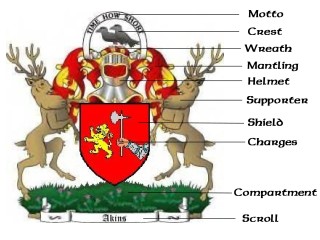

The system of blazoning arms that is used today was developed by the officers of arms since the dawn of the art. This includes a description of the escutcheon (shield), the crest, and, if present, supporters, mottoes, and other insignia. An understanding of these rules is one of the keys to sound practice of heraldry. The rules do differ from country to country, but there are some aspects that carry over in each jurisdiction.

Though heraldry is nearly 900 years old, it is still very much in use. Many cities and towns in Europe and around the world still make use of arms. Personal heraldry, both legally protected and lawfully assumed, has continued to be used around the world. Heraldic societies thrive to promote understanding of and education about the subject.

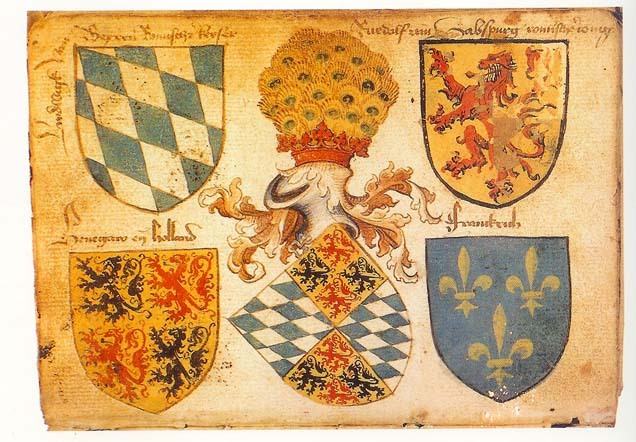

The beginnings of modern heraldic structure would not become standard until the middle of the 12th century. In the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, heraldry became a highly developed discipline, regulated by professional officers of arms. As its use in jousting became obsolete, coats of arms remained popular for visually identifying a person in other ways—impressed in sealing wax on documents, carved on family tombs, and flown as a banner on country homes.

For the purpose of quick identification in all of these, heraldry distinguishes only seven basic colors and makes no fine distinctions in the precise size or placement of charges on the field. Coats of arms and their accessories are described in a concise jargon called blazon. This technical description of a coat of arms is the standard that must be adhered to no matter what artistic interpretations may be made in a particular depiction of the arms.

The idea that each element of a coat of arms has some specific meaning is unfounded. Though the original armiger may have placed particular meaning on a charge, these meanings are not necessarily retained from generation to generation. Unless the arms incorporate an obvious pun on the bearer's name, it is difficult to find meaning in them.

Rules of Heraldry

Shield and lozenge

The main focus of modern heraldry is the coat of arms (Note: This is distinct from an armorial achievement, which is the coat of arms plus other elements, such as supporters). The central element of a coat of arms is the escutcheon. In general the shape of shield employed in a coat of arms is irrelevant. The fashion for shield shapes employed in heraldic art has generally evolved over the centuries. There are times when a particular shield shape is specified in a blazon. These almost invariably occur in non-European heraldry.

Traditionally, as women did not go to war, they did not use a shield. Instead their coats of arms were shown on a lozenge—a rhombus standing on one of its acute corners. This continues to hold true in much of the world, though some heraldic authorities make exceptions. In Canada the restriction against women bearing arms on a shield has been completely eliminated. Noncombatant clergy have also made use of the lozenge as well as the cartouche – an oval – for their display.

Tincture

The first rule of heraldry is the rule of tincture: metal should not be put on metal, nor colour on colour. This means that or and argent (gold and silver, which are represented by yellow and white) may not be placed on each other, and neither may one of the colours (tinctures that are neither or nor argent) be placed on another colour.

Tinctures are the colors used in heraldry, though a number of patterns called "furs" and the depiction of charges in their natural colors or "proper" are also regarded as tinctures, the latter distinct from any color such a depiction might approximate. Since heraldry is essentially a system of identification, the most important convention of heraldry is the rule of tincture. To provide for contrast and visibility, metals (generally lighter tinctures) must never be placed on metals, and colors (generally darker tinctures) must never be placed on colors. Where a charge overlays a partition of the field, the rule does not apply. Like any rule, this admits exceptions, the most famous being the gold crosses on white chosen as the arms of Godfrey of Bouillon when he was made King of Jerusalem.

The names used in English blazon for the colors and metals come mainly from French and include Or (gold), Argent (white), Azure (blue), Gules (red), Sable (black), Vert (green), and Purpure (purple). A number of other colors are occasionally found, typically for special purposes, including the stains Tenne (brown-orange), Murrey (maroon), and Sanguine (brown-red).

Certain patterns called "furs" can appear in a coat of arms, though they are (rather arbitrarily) defined as tinctures, not patterns. The two common furs are ermine and vair. Ermine represents the winter coat of the stoat, which is white with a black tail. Vair represents a kind of squirrel with a blue-gray back and white belly. Sewn together, it forms a pattern of alternating blue and white shapes.

Heraldic charges can be displayed in their natural colors. Many natural items such as plants and animals are described as proper in this case. Proper charges are very frequent as crests and supporters. Overuse of the tincture "proper" is viewed as decadent or bad practice.

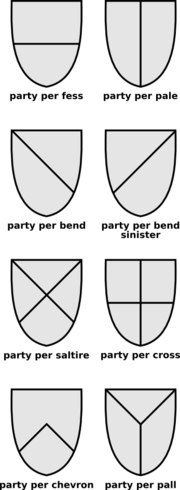

Division of the field

The divisions of the field is a heraldic term referring to the pattern on a shield. The field of a shield in heraldry can be divided into more than one tincture (as can the various charges). The divisions are (almost without exception) named according to the ordinary that shares their shape. (It should be noticed that French heraldry takes a different approach in many cases than the one described in this article.) Common partitions of the field are: parted (or party) per fess (parted horizontally),

- party per pale (parted vertically),

- party per bend (diagonally from upper left to lower right),

- party per bend sinister (diagonally from upper right to lower left)

- party per saltire (diagonally both ways).

- party per cross or quarterly (divided into four quarters)

- party per chevron (after the manner of a chevron)

- party per pall (diagonal divisions from upper left and upper right meeting vertical division)

A field cannot be divided per bordure (as if this did exist it would be indistinguishable from the bordure); though a bordure can. Neither can a field (nor any charge) be divided per chief, for similar reasons. A shield vertically divided into blue (left side) and gold (right side) would be blazoned: Per pale azure and Or. When a field is quartered in a swastika-like pattern, this is called quarterly en equerre. Use of a swastika-like form in heraldry is called the fylfot and long predates any fascist associations. German heraldry, unlike British, acknowledges the form per bend... broken in the form of a linden leaf.

Links

Pages in category "Heraldry Terms"

The following 33 pages are in this category, out of 33 total.